This is a subjective summary of discussions that we’ve been having amongst AngryWorkers on the war in Ukraine. The discussions have been quite emotional and personal at various points. I will try and trace some of the controversial bits as best I can and invite other comrades to comment.

Before looking at the open and contentious questions, there is stuff that we agreed on. We agreed that we should do our best to support anti-war protestors and deserters in Russia, to support workers in Russia who go on strike against the economic fallout of the war, and refugees from Ukraine who want to escape the war. We want to support all those workers who refuse to handle bloody goods, like the UK dockers who refused to unload oil from the Russian state. This is why we signed up to the call by the Transnational Social Strike Platform as a minimum, though somewhat pacifist, platform of common action, and hope to collaborate practically.

When trying to understand the controversial arguments, perhaps it is helpful to look at what we thought our common position was when it comes to capitalist wars and how this assumed common position clashed with the concrete situation of the war in Ukraine. I think it is fair to say that we generally assumed that, “workers’ should not fight their bosses’ war” and that, although being a very blunt verbal uttering, “no war, but the class war” could express our general political line. We still carry shreds of the umbilical cord that connects us to the backrooms of Zimmerwald and other communist internationalists in the past.

I think we were on a similar page once it comes to understanding the bigger picture of the war in Ukraine. We know about the Nato expansion and the attempts of the US state to drive a wedge between Russia, China and the EU. We know about the ambition of the Russian state to become the policeman of the eastern hemisphere, its crude totalitarian export regime. We are in no doubt that all these rivalries, aggravated by the global crisis, play out in Ukraine.

But what exactly is a ‘bosses’ war?’ And what use is an internationalist principle if your village is being shelled by a Russian tank? To what extent do workers in Ukraine just have to defend themselves against a military aggression? We approached this question on three main levels.

The first level addresses the question in the most immediate sense: direct self-defence. We asked ourselves whether people have an actual choice as to whether they take up arms, or whether taking up arms is not something that is imposed on them by the situation. Could we tell people in the Warsaw ghetto, in Srebrenica or in the moment of an ISIS attack not to take up arms, because their arms might be supplied by nationalists or that their resistance falls in line with the interests of one of the big imperialist powers? I guess we can’t. But then is (or was!) the situation in Ukraine a situation of ‘fight or be killed’ in a very immediate sense? With a strategy of the Russian state to portray the invasion as a ‘liberation’ welcomed by most Ukrainians, the Ukrainian state has an interest to show that there is resistance. Some civilian deaths will come in handy to demonstrate this. Flames need to be stoked and they are stoked easily. There is that danger. There is also the danger of missing a chance to fraternise with the young working class Russian soldiers. Nationalist gangs or the regular army won’t have an interest in even trying.

The second level addresses the question of self-defence in a less immediate sense. Would we not see a row of Russian tanks driving towards the government building in Kyiv as an attack on the future freedoms of workers? As working class people, it might be better to live on the EU side of things, with access to better labour markets and with more personal liberties (- unless perhaps you work in steel plants or mines that would most likely be closed down with further market liberalisation). But this is not just a rhetorical question: many working class people who have decided to take up arms won’t have done so either because they ‘just want to defend their homes’, nor because they are deep-rooted blood-and-soil nationalists. They are not stupid. They know that life on the western side of the curtain will be better.

Even from a broader political point of view, we could say that the best possible outcome of the war both for the local and international working class is the defeat of the Russian state as the immediate aggressor, the fall of Putin. I don’t say that because I particularly love the EU, but because of what has happened in Kazakhstan recently, where Russian tanks were used to suppress a popular uprising. And of course in Syria. But the question is, how can the Russian state be defeated? Here things start to slide down the slippery slope. Realistically the Russian state will only be defeated militarily once the Ukrainian army gets further military support from Nato, (which is already happening) and under serious nuclear threat, which risks the war spiralling out of control. Would that empower the global working class? Sanctions will either not have a heavy enough impact (or if they do, will mainly worsen the conditions for workers in Russia), or, given the dependency on energy supply from Russia, will be implemented half-heartedly by EU states (e.g. with loopholes). In that sense most lefties quickly call for ‘no fly zones’ or actual military support of the Ukrainian army. This falls in line with the interests of, e.g. the new German militarism in the form of the social democratic – Green – liberal government that just voted through a 100 billion Euro rearmament program. FYI, it is the Green Party in government, like during the Yugoslav war. The ‘alternative’ to direct Nato involvement is a long drawn out ‘home grown’ war with thousands of deaths, which might result in a slow attrition of the Russian war effort. But this ‘resistance’ will be fully in the hand of the nationalist forces. They might win, in a blood bath – and probably agree to a divided Ukraine. That is half a defeat for Putin and a full defeat for working class internationalism.

The Yugoslav war is a good example to discuss the situation in Ukraine. Some of our comrades were closely involved at the time, trying to organise practical working class solidarity. We had a similar build up of financial and political encouragement of nationalist tendencies in Yugoslavia in particular through Germany and Austria. This background story is often forgotten and the focus is on the ‘black box’ of the war, the ‘ethnic rivalries’. That allowed the government in Germany, the Green Party foreign minister, to justify military intervention as a way to “prevent a new Auschwitz”. Left cover for brutal market liberalisation. The ethnic massacres were not actually prevented, but some of the states of former Yugoslavia are now EU members, supplying cheap labour or providing locations of profitable investment. From an ‘individual’ workers point of view, at least in Croatia or Slovenia, their condition might now be better than under ‘Yugoslav’ rule, both economically and politically – but at what cost if we see it in perspective? Thousands killed, deepened nationalistic divisions within the regional working class…?

There is a certain strand of ‘objective progressivism’ within the left that also reverberates within AngryWorkers. “The defeat of the Russian state will objectively be better for the wider working class. The EU is better than a backward dictatorship. Being part of an advanced economic block with a wider range of democratic rights benefits the possibility for the working class to fight future struggles. In the absence of revolution workers should attach themselves to the capitalist block that provides a better foundation for future struggles.” Given the lack of an independent working class movement, this type of thinking is attractive. The problem is that in the medium and long-term it prevents the working class from developing the required independence. What else happened in 1914? The SPD argued that a war against the Czar’s regime will further the cause of a modern working class movement and that war credits should be granted – in a way this was not a betrayal, but just an example of taking this political approach to its practical conclusion. This has been repeated in various ‘liberations’, where the workers had to side with the ‘progressive’ segments of the bourgeoisie, from India’s so-called Independence to the anti-colonial struggles in the following decades. More recently I encountered similar arguments during the US gulf war in 1990/91. ‘Progressive’ German leftists argued that Saddam is a nutcase, anti-semite and mass murderer (which he was!) and that the US spreads advanced capitalism around the world, which is the only material ground for thinking about communism. Therefore, the peace movement was petit-bourgeois and we should stop occupying our school.

But then the situation in Ukraine is different. This is where the third level of the debate comes into play. We asked ourselves whether in the (armed) resistance itself, both on the level of immediate and wider political self-defence, there is space to develop experiences of solidarity and anti-authoritarian community. And we do hear a lot about neighbourhood support, about acts of solidarity amongst strangers and the formation of independent fighting units. The question here is whether there is a material and political foundation for these spaces not to be swallowed up by Ukrainian nationalism, the mafia, the strong-man, the imperialist powers. Where do the weapons come from, who has the fighting experience? Our comrades from Poland report that the prices for weapons and equipment, such as helmets, have gone up sharply – there is little chance of independent rearmament. Azov fascist paramilitary units are integrated into the regular army and receive modern weapons and instructions through Nato-linked channels, financed by Ukraine’s oligarchy. The ‘community’ might as well be coined in a cross-class national sense, with local businesses helping out. I personally think there is no way that without a prior formed working class unity and political clarity this ‘anti-authoritarian’ spirit can develop in a situation where the balance of forces is totally tilted towards the Ukrainian state forces and nationalists. This is not Spain in 1936. But then it never is and we cannot just recline in our defeatist armchair. Perhaps we have to accept that the working class will not gradually rebuild its strength through industrial disputes, but also has to recompose itself in these messy situations…?

What would the alternative be? Is it realistic to advise workers in Ukraine to just let the Russian state impose its puppet government and then fight for your freedom ‘on workers’ terms?’ Can you just re-group under conditions of an imperial police state? Did you miss your chance to fight for the necessary breathing space? History has examples for both. There were many situations where worker militants ended up isolated or incarcerated or in exile, because they avoided the confrontation, hoping for a more opportune moment. Then there have been many examples where workers did manage to fight police states ‘on their own terms’, like in South Korea or Brazil in the 1980s, without much bloodshed and nationalistic bullshit. Perhaps that’s what workers in Ukraine will have to go through, they might have to lay low and weather the storm of the war and fight the occupying Russian state on their own terms, rather than risking escalating warfare under national bourgeois leadership. But this is a speculative choice, given the absence of a collective subject that would be able to chose: who are ‘the workers in Ukraine’? Perhaps the fact that over 2 million people have left the country is part of this choice.

While initially the question ‘what would you do if you were in Ukraine’ was productive, it also quickly turned into a bit of a depoliticised dead-end. What can you do if there is no working class movement on the ground? This is how we ended up supporting the general ‘pacifist’ efforts, with an awkward ‘working class’ add-on. I personally asked myself what I would like to tell my colleagues in the hospital where I work about the war. I had a discussion with a fellow low-paid porter from Poland who said: “It’s good that the German government now spends more on the military. This is needed in the world we are living in, you can see it in Ukraine”. The leaflet draft below is a thought-experiment: what do we have to say, not to each other or other leftists, but to our co-workers? Admittedly, it might be pretty lame to read, but it’s also an expression of objective helplessness. How can we actually, practically rebuild working class internationalism, beyond stale principles? The left slips into the two opposing camps quickly (pro-Putin/ pro-Independence), and the tiny voices that call for working class unity and system change are hardly heard. What kind of actions – of self-defence, support etc. – facilitate that this voice is heard and what kind of actions drown it out or contradict it?

Leaflet draft…

——

From crisis to war – How to find a way out?

Like workers elsewhere, we’re just coming out of the pandemic and now we’re confronted with the danger of escalating war in Ukraine. We have our own day-to-day battles going on that tire us out. Some of us have lost our jobs during the pandemic, others were overworked, now we all face rising living costs. Do we even have the head-space to think about the war?

If we want or not, we are connected to this war. As humans, who see others suffer. As workers, whose wages are eaten up by further increases in energy and food prices as a result of the war. As possible future victims if things escalate further. But in a way, we’re even more deeply tied up in the situation.

In a society where everything has a price tag and is sold on the market – from labour to food to weapons – war can be good business for some. Most EU countries trade arms with Ukraine and, at the same time, gas and oil with Russia. Nation states compete on these markets and frequently this competition turns into war.

We live in a society where the potential for a good life is turned against us. New technology leads to job losses and more stress at work, because it is used not in our interest, but for profits. While poverty increases, billions of dollars, euros and rubles are spent on war machinery. How can those in power defend this madness, which grants them privileges and profits? By creating external enemies. Workers in Russia are surely not happy, neither are workers in Ukraine. But instead of getting rid of their rulers they are now caught up in war.

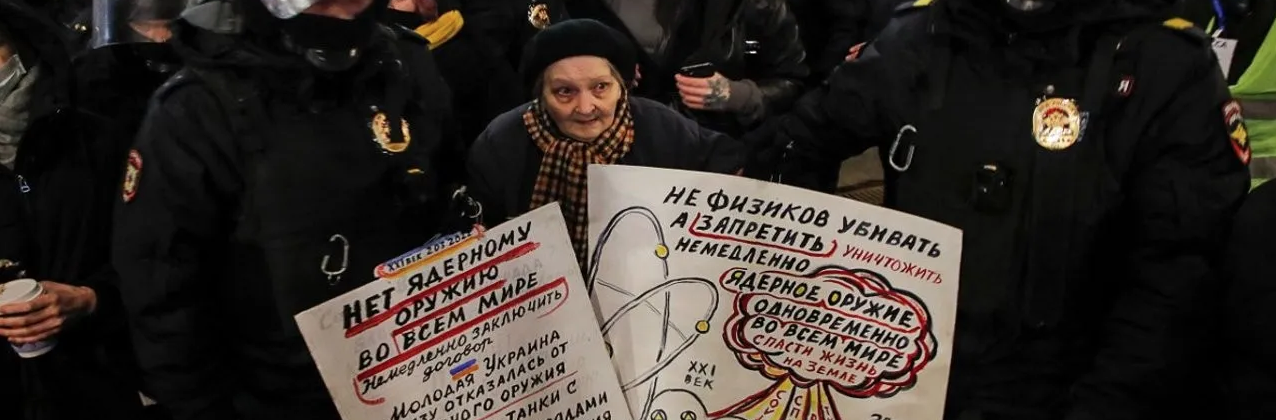

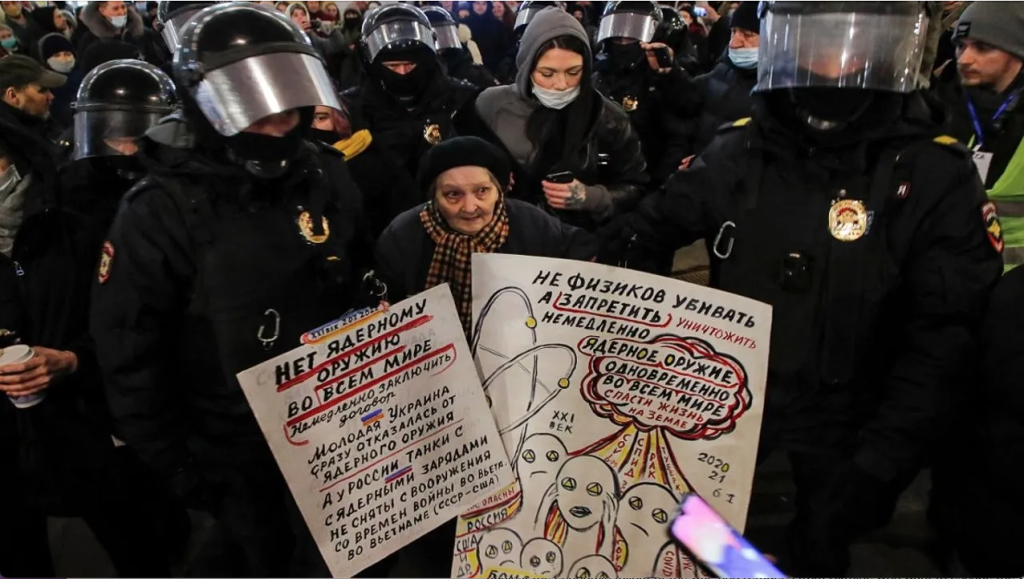

It was an international workers’ revolt that ended World War I. We now need a workers’ revolt to prevent World War III. We can support our brave sisters and brothers in Russia who protest against the war, risking arrest and prison. We can support the thousands of teachers in Russia who publicly refused to teach Putin’s version of the war. We can support workers in Russia who are currently on strike due to unpaid wages, another result of the war. We can support those who refuse to fight in either of the warring armies and try to get out of the country. We can support workers in Ukraine who try to resist both the military occupation and to be drawn into a nationalist bloodshed. We can support those many dock workers who refuse to load and unload oil from Russia or cruise missiles for export to Saudi Arabia.

Our best support is to fight for a better society here, where we are. We need a society of solidarity and collaboration, where it is us who decide how and what we produce for a better life, not the markets, profits and warlords. Stay together, against evictions, wage cuts, deportations and other attacks on us as workers!